Futurescape Tokyo is

a study in urban

fantasies and speculative

cartography. The project aims

to explore potential future

scenarios of the world's

largest megalopolis Tokyo,

which is expected to

shrink dramatically

during the next 86 years.

INTERVIEWS & MAPS

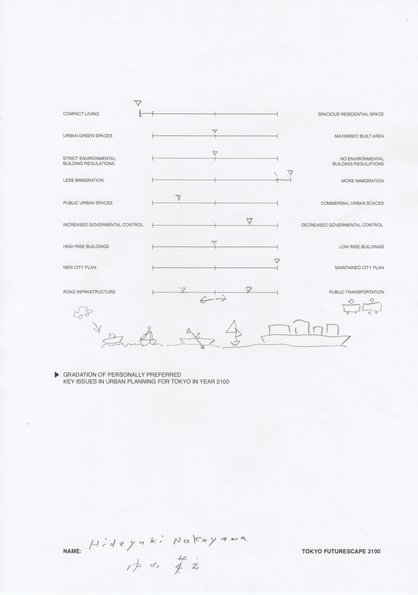

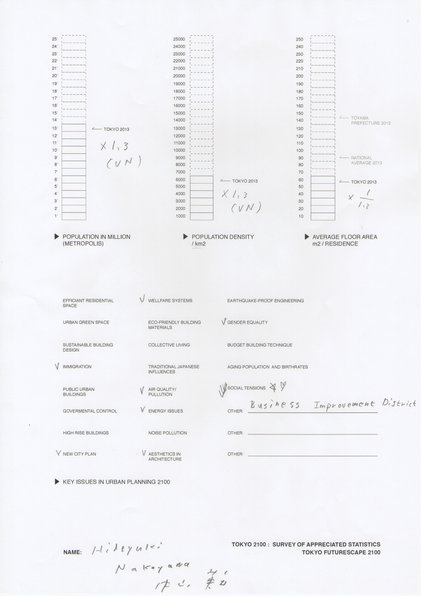

HIDEYUKI NAKAYAMA

The award-winning Japanese architect Hideyuki Nakayama is known for his original use of space and depth in residential projects, such as the O-House and the Y-House. With an innovative, minimalistic design of private houses in an urban context, he expresses an interesting interpretation of how the private sphere meets the public cityscape. After graduating from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Hideyuki Nakayama spent seven years working for Toyo Ito & Associates. Since 2007 Hideyuki Nakayama is running his own studio in Tokyo, located inside a low brick building in the quiet Sendagaya neighborhood. We knock on the door on a cold winter day. It is flu season and the office is almost empty. The textile artist Akane Mariyama is our companion and helps us to interpret between English and Japanese. Akane is the designer of the hand made full length curtain that is clothing the large, floor to ceiling window of Nakayama's O-House.

Do you think the current projection is correct, that Tokyo's population will shrink to half by year 2100?

The population of Japan is decreasing year by year, but Tokyo is still growing. So the contrast between the megalopolis and the countryside is very, very high. I don’t think that Tokyo will shrink in the future. A lot of people are coming to Tokyo from everywhere. From Asia, from Europe. Right now there is a huge expo of anime culture. People come from Russia, Seoul, America, wearing costumes inspired by the anime characters. They all gather in Tokyo around the same culture.

Before, the children in one school used to share a common culture. We watched the same tv shows, we were interested in the same kinds of things, and so on. But nowadays, children do not do that. They have their own favourite things. A girl might not find friends in her own classroom that share the same interests as her – but she could find a friend with the same hobby in a Russian classroom instead. They become like "invisible classmates". So, on that micro level, the classroom, the world is diverse, globalised and mixed up with different cultures. However, if you look at the macro level, the world is becoming flatter. You find the same things everywhere. Starbucks, McDonalds, H&M. The same in Paris, Sweden and Tokyo.

How would you describe Tokyo as a city today?

It is a city of events. If we recall the relation between the "invisible classmates" in Tokyo and Russia, you can see those comic art events as a physical space for the “invisible” classmates to gather. That is amazing! Many Russian girls do not find friends in their classroom that share their interest for anime culture, for example, but since the anime-kids are not geographically based, you can find them somewhere else on the planet. And now the invisible classmates gather in a place… and that place is Tokyo! It is a huge event, so many boys and girls meet at the same place. I think this gives hope to Tokyo.

What are the main challenges for Tokyo in the near future?

When it comes to political issues, one big challenge is how many immigrants that can come to Tokyo. It is not something we can solve individually, it is a political issue. When it comes to architecture and city planning, I am interested in suburban space. For example, there are a lot of illegal immigrants in Tokyo, especially from Brazil. They are living at the bottom of the hierarchy. They are working at construction sites for example, and are an important part of the economy. But because we do not accept immigrants legally, and they are not supposed to be there, people do not talk about it. The most important issue is that their kids do not get a proper education. That is a big problem.

In previous interviews you have talked about your interest in urban meeting spaces and social spots in the neighborhood. Are there any good examples of such social spots and public meeting places in Tokyo?

There used to be a walker's sanctuary in a huge road in Harajuku on Sundays. This was in the 80s and early 90s. Young kids gathered to dance and play music. There are no residential houses surrounding the street there, so many musicians used to gather around a car with a huge amp, shouting and rocking every weekend. The reason to why it does not exist anymore is very boring; traffic jam problems and that the elderly did not like that kind of culture. So it stopped.

How do you work with these kinds of social issues in your architecture?

I made a very, very small building for a real estate agency. It is placed in a corner where there used to be a gas stop before, and it faces the sidewalk. Usually, gas stops are an just open space with a roof. So I made the walls transparent and the floor is made out of the same material as the pavement outside. The boundary between the public space and the private disappears. It looks like an open floor building. So, the place is actually almost the same as when there was a gas station. What changed really? Just the name. It used to be a gas stop, now it is an office building… it is just a matter of a title. The space is the same. If a person stand there and play the guitar, the space turns into a stage. The public space is not in fact decided by the boundaries written by the government. The boundaries are made by the person who uses the space. This is something people forget about. We can dance on the street, go skateboarding and play music like in the 80s. But people think unconsciously that this is not something we can do.

Statistically, it is probable that Tokyo will suffer from a new big earthquake before year 2100. How do you think Tokyo will rebuild after that? Will it be rebuilt on its old patterns or will the city's structure change?

It is a really difficult question. I think it might become more like during the Edo period, with the canal. Every building next to the canal, had the entrance facing towards the water. That is the typical scenery of the Edo era. In school they taught us why the canal disappeared. They said it was because a shift from shipping to modern transportation. But the true story is different from the official one. After the WWII, a huge earthquake destroyed many, many buildings and the canal was filled up with wood from the demolished buildings. Because it was difficult to take care of all the destroyed houses, they just filled up the canals.

I think the city will go back to using canals like during the Edo period, because the means of transportation is changing. I think that the number of cars in the future will decrease. Many Japanese car companies are trying to develop automatical driving systems. With auto drivers there will not be any traffic jam, since the traffic will be so smooth. Other transportation systems, like the trains, will also be developed and become more advanced. So we will not need so many cars in the end.

Do you think canals will be used instead of cars?

A road will be destroyed in an earthquake, while water is very, very soft. If the city want to keep some buffer space in case of a disaster, a canal network is very good for that. It is flexible in many ways. Transporting things on a boat is much more efficient than on the road. Actually, the Tokyo municipality is using some boats to transport garbage even today. It is much more efficient than cars.

There is a very, very popular book called "The little House" by Virginia Lee Burton. The story is very interesting. It is about a small house in the countryside. Life is sunny and follows natural cycles. But one day, a road is built around the house. And then a whole city appears. After many years, the great-great-grandchild of the original owner finds the house in the middle of Manhattan. She recognizes it from an old picture. So she buys the house and transports it to a new place in the countryside, similar to the original one. It is sunny and surrounded by nature. And then! Haha. A road is built. And it starts all over again. This book is written in the 30’s. The story represents a cycle of a 100 years. So, right now in our time we live around 70 years after the first page in the book. And that is a very dark page! It is quite scaring. But maybe it will all start over again, like in this book. Can we find the next space to move to?

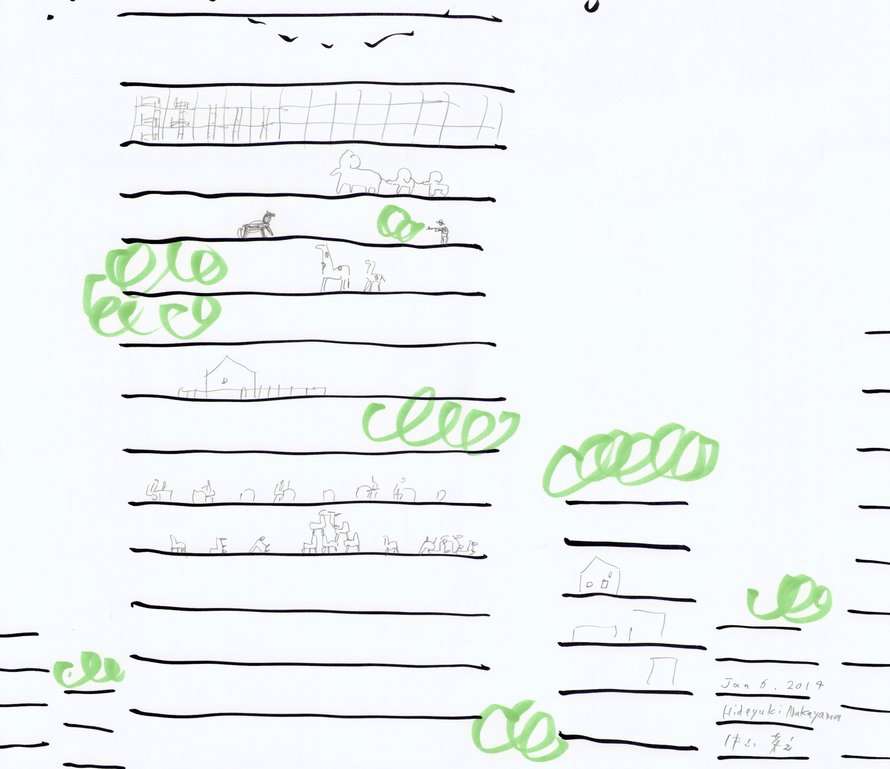

TOKYO'S FUTURESCAPE ACCORDING TO NAKAYAMA

After a huge disaster, the grass has started to grow. Roppong Hills looks like a jungle. Floor 31 is a jungle, floor 32 is occupied by bedrooms, 33 is a skateboard paradise. And one floor is an office space. People have forgotten about the meaning of the building and find new ways to use them. Like Bruno Munari, in his chair. Buildings never make a city, a city is made by humans and they find their way of using the space. The kids in the future will use the buildings as Munari used the armchair.

Hideyuki Nakayama