Futurescape Tokyo is

a study in urban

fantasies and speculative

cartography. The project aims

to explore potential future

scenarios of the world's

largest megalopolis Tokyo,

which is expected to

shrink dramatically

during the next 86 years.

INTERVIEWS & MAPS

HEIDE IMAI

German architect and urban researcher Heide Imai came to Tokyo for the first time ten years ago, to do research for her thesis. She wandered the alleyways of Tokyo, observing and documenting the everyday life stories that took place in the gap spaces, in-between the buildings. Today she lives in Yokohama together with her Japanese husband and their three-year-old son. She works as a researcher at the Keio University and teaches courses in critical urbanism, urban planning and social research methods at various universities across Europe and Japan. A recurring theme in Heide Imai's research is the value and meaning of marginalized street space. How are small urban places affected by re-development, gentrification and commodification? What role do Tokyo's traditional alleyways – the rojis – play in the city today? We meet up on a sunny January morning in the very center of Tokyo – the bustling, twinkling, howling Shibuya. Heide Imai guides us through the crowds, in among the alleyways, to a little café. We sit down for a chat over a cup of sencha.

How would you describe the city of Tokyo today?

Tokyo is a city of many opportunities. However, if you want to make it here, you have to search for your own special niche and dive into it whole-heartedly. In that way, Tokyo really is what you make out of it. You have to be able to just let go of everything you had in the past and just dive into that place of opportunities. Then everything is possible.

What do you think is Tokyo's biggest challenge at the moment?

I think one of the biggest challenges is to enable people to create more stability in their lives. This is critical, I think. If people don't find stability, eventually they will turn away.

People need a stable life situation in order to find balance between work and family life. In terms of affordable housing, for example. A family friendly environment, more green spaces. I personally would prefer a city with less focus on shopping, but with a much greater sense of community. In general, I would just like more focus on us – as neighbors and fellow citizens – and not only on me. This is unfortunately the main problem that I see right now in Tokyo. The me-culture, the me-generation.

I think Tokyo should avoid to take over the American, western, model of globalization, with franchises and so on. Of course the globalization will affect the whole world to some extent, but in my opinion Tokyo should work more on what can be the Japanese version of that global culture.

Tell us about your interest in the vernacular and the alleyways of Tokyo!

When I first came to Tokyo, I was interested in documenting the stories that hid in the gap spaces, in-between the houses. The everyday life taking place in the seemingly empty and unremarkable spaces. But then, after a while, someone told me: "You know, there are not only gaps between the houses – there are also alleyways. Why don't you look into what the alleyways are all about?". Because a gap is just a gap, a void, whereas a back street might have more history. And that is when I started to do research on the roji, which is the Japanese term for alleyway.

Nowadays I write less on that specific urban form, and more on the revival of vernacular landscapes and items. I look for what used to be typical in the past. It is quite difficult to distinguish nowadays what was once typical for Tokyo, or Kyoto, or Nagoya, or Osaka, because there are more layers now. But there are elements. There are still inscriptions of the past in the city, even though the city in itself is transformed. In that way, my work resembles a little of archeology. I look for remnants in the city of the everydayness of the past. I am interested in the urban morphology of a place. The patterns and social structures that continue to shape the modern city.

What are you looking for, more specifically?

I ask myself – what is the character of this neighborhood? What realities have shaped this specific urban area? If you visit a dense area in the old Edo-part of Tokyo for example, you will find many layers. You might find the overlapping realities of the merchants or the warehouse people, or the servants of the palace – and then also of people like the samurai and the daimyo.

And somewhere in the city, these realities overlap. And then suddenly you realize that there are not only these big plots of the daimyo, but there is also a tea ceremony area, where geishas are still practicing! And then, on top of it all, you might see a big high rise building, which is there because a temple once sold a huge plot of land to develop... What is this? Is it globalization? Is it gentrification? Big question.

What lost qualities of urban life do you miss in Tokyo?

Many things have disappeared. The public bus for example... Children don't play outside anymore, they stay indoors... The “idobata-kaigi” or the “genkan talk”, when people used to stand in the hallway or entry of a house, just to chitchat and gossip about nothing in particular. All these things have disappeared! Some things remain though. People still play music in the streets. And there are also new ways of doing things, such as the park benches for old people. So, not everything is disappearing, but they might be remembered in a new version.

This kind of transformation is not only negative, as I see it. Change is unavoidable, sometimes you need to get rid of something in order to create something new. What is important is to take advantage of the qualities of a place. Don't just get rid of the old but try to use it in new ways. I like the old slogan "reduce, recycle, reuse".

What does the slogan "reduce, recycle, reuse" mean to you?

Tokyo should not only focus on quick money and tear down old beautiful houses just to build yet another shopping mall. Instead, use the existing qualities in innovative ways, to make it useable again. For example, a person I know opened a Bossa Nova Café in Ueno, together with some friends. They used to study art in the area and wanted to stay, so they rented an old house and started a business that they felt was close to their hearts. Bossa Nova has absolutely nothing to do with the traditional life style of Ueno, but it can still contribute to the neighborhood by keeping it alive. I think things like this are the new chance for many neglected areas.

Can you give us some examples of how people have regained forgotten spaces and reevaluated them in Tokyo?

There are quite a few examples of art and design actors who "recycle" old buildings and use them as art galleries or venues. The old abandoned bath houses of Tokyo is a good example. The most famous one is probably the Scai The Bathhouse in Yanaka, now redeveloped into an art gallery. Yanaka is a good example of a neglected area that has been able to reinvent itself.

Another example is an old school in Taito-ku, which had to close down because of lack of students. But instead of demolishing the building, they decided to transform the school into a designers village and a kind of incubator for young designers. This also had a spreading effect on revitalization in the area, with young people moving in and in their turn attracting new people, and so on.

Kiyosumi-Shirakawa, east of Sumida river, is another area where many galleries have opened in old factory buildings in recent years. And while these young artists might not feel part of the traditional life style in the area or attend the meetings of the neighborhood association – still, they somehow contribute and give life to the area. They reformulate what kind of place this is.

Some people we have met here in Tokyo talk about a shift in attitudes in the Japanese society after the catastrophes in 2011. Do you think people are more conscious than before about political issues and the surrounding environment?

I do see a shift in attitudes. When I talk to young people, like my students, many of them express a wish to escape the typical salarymen life style of Tokyo. They know what is expected from them, but they are not happy with it. So they search for a deeper meaning. However, I think this trend it started already before the catastrophes. If you move to Tokyo and wish to make a life here, you have to ask yourself – how can I do it and at the same time keep my happiness? How do I keep my work-and-life-balance?

You were talking about the "me-culture" earlier. Maybe this individualism is challenged by a simultaneous trend of sharing more, gathering more?

It is possible that this kind of doubts and ruminations come up to the surface in times of crisis or recession. Maybe people start to question themselves and their society more.

How has the view on architecture and urban planning in Japan been affected by the catastrophes?

Of course there are various rebuilding programs and urban planning initiatives. Many architects rushed to the disaster-stricken areas and started up projects. But, has the mindset changed? I don't know.

People from outside of Tokyo often blame tokyoites for being egocentric, for focusing only on the Olympics and on what Tokyo needs, and to little about the Tohoku area and the rest of the country. And there is some truth to it, I think. A lot of people never see other parts of the country, they don't care and they don't even want to know what is going on. And even if they are aware somehow that also Tokyo is very vulnerable geographically and that there is a constant risk for a tremendous earthquake to happen, it is not something people think and talk about a lot. Maybe this is what you have to do, shut it out and just not focus on it.

It you look at the history of Tokyo, you can see that this city has been destroyed many times and then rebuilt more or less on the same grid, but with new buildings. If – or when – Tokyo suffers from another big earthquake, what principles do you think should guide the rebuilding of the city?

I think that the understanding of rebuilding and preservation, should be less based on the material aspects and more on the skills. This is something people often forget about. The unspoken wisdom of a society.

During the Edo-era this was a much more sustainable town than it is today. For example, human waste was used as recycled energy. Why don't we incorporate this effective system again? Maybe it doesn't sound very attractive, but you you can grow all the vegetables you need in Tokyo, in the urban

area. But we don't. We import, and we have a huge amount of waste. Why not incorporate the wisdom of Edo, in the Tokyo of today?

Societies always go through cycles of forgetting, remembering, re-embracing... But I think that if you want to recreate a city that is more resilient, more sustainable and more livable, this is what you have to do. Rediscover the local wisdom, the local systems and rules, and incorporate them in the modern world. There is no need to reinvent everything.

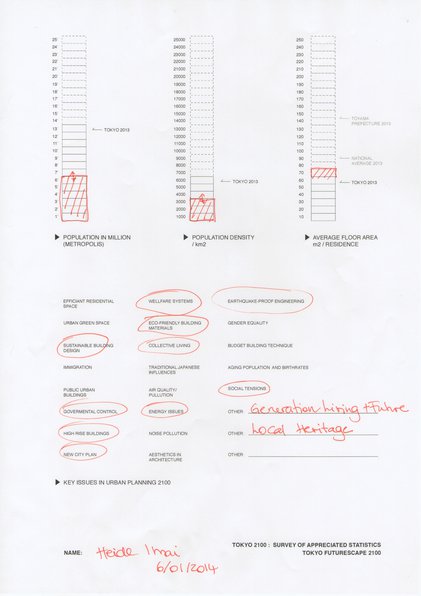

According to a recent prognosis, the population of Tokyo will have decreased to half of its current size by year 2100. Do you think this rapid shrinkage will really happen?

Well... I can not imagine that Tokyo would find a solution to the falling birth rates. Just as little as Seoul or Hong Kong or any other city in the same situation. So, the only solution would have to be either accepting highly skilled immigrants, or immigrants who can fill the low-skilled jobs. But in that case, the Japanese society would also have to become more open-minded towards the fact that not everybody might learn Japanese perfectly, and so on. And that, I don't see coming in Japan.

So, you don't see immigration as an option?

Of course it would be ideal. But I do not see it coming. Maybe if it was already happening to some extent, but as it is now... foreigners are still very much excluded in Japan. I mean, if you have a really, really strong wish to live and work here, and you make the effort to learn Japanese and you figure out the social codes and patterns – then sure, it is possible. But you will never be a hundred percent accepted. As an immigrant in Japan, I know that I will always be different. All my life, as long as I live here, I will be special. For me this is actually okay. I don't mind, I don't want to become Japanese. It is not my aim in life. It can even be nice to be different sometimes, because in Europe I sometimes feel so ordinary. But to some people, this is not enough to live a good life. If you don't know the language you can feel like an an-alphabet, or like a child in some ways. Not being able to help your child in school. Things like that. The point is, if you need immigrants and wants to attract them, then you have to become more open towards differences. You must make it possible for them to be part of society. I think immigration will surely happen to some scale, but it will not be enough to solve the problem with a shrinking population.

Let's say then that Tokyo will shrink to half, as the prognosis says. Do you think shrinkage could have positive aspects? Can it be turned into something good for Tokyo?

It is a good question. Maybe we have the opportunity now to create a sustainable shrinkage in Tokyo. Shrinkage to a size that is more sustainable than today. Maybe Tokyo can become a highly sustainable and efficient society, on a much smaller scale than today. I don't want to say a new version of Singapore, but highly specialized in one or two fields. With more backlands, which are taken back by nature and greenery.

How do you think urban functions can be used to manage big social changes like this? In this case, a rapidly shrinking and aging population.

Of course, higher technology will allow people to get older. The baby boomers will become very old, and this will be a huge economical burden.

To some extent, we will find some balance. There are creative solutions already, such as combinations of kindergartens with elderly care. I think this is what we have to get creative about. Connect two problems with one another to find a solution.

Imagine you got free hands. How do you think Greater Tokyo should change during the next 86 years, in order to handle the shrinkage in a good way?

Today we have a population of 35 million people. Let's say in 2100 we will have a population of maybe more sustainable 16 million. Would it mean fifty percent more green space? Or a maximum of eight floors? Why not! I think this is a more human scale, it enables you to know who lives under and above you. In German there is a word for this: "rückbau". It means something like "de-crease" or “de-growth” and refers to the downsizing of a city in sustainable ways. For example, recreating greenery, rooftop farms, vertical facades... Tokyo might have enough space to build baseball fields or soccer fields in the middle of the city. Or hospitals can have access to recreation areas in the city center. It would be a good option!

So, what do you think Tokyo will look like in 2100?

I think there will be more greenery. There will be less people. To some extent people will still face loneliness or hardship, but there will be more opportunities, hopefully. Because there is more space available. There will be more voids and more occasions... and also less money. Hopefully people will reunite and live closer to each other. There will be various subcenters, and other areas will be very empty. But maybe people need that place, space, of contemplation. Today in Tokyo, there is almost no space where you can just be by yourself, so maybe that space will provide people with a healthier mindset.

Is this what you hope for?

I would hope for much more, of course. Young people, and lively people. But let's face it, that doesn't seem to be the case. But with more space, or more opportunities... I hope people will use it wisely. I hope they will use the opportunities to rediscover themselves and the local wisdom, in order to create a sense of community. Whatever community is then. That would be what I hope for.

And even if Tokyo is shrinking in 2100, as we all predict, it might still be made up of maybe 50 or 20 urban villages. Communities that are urban and cosmopolitan, but at the same time they are also villages. I also think there will be more generational living. And something I would really like to see, is sustainable low-energy houses, made of eco-friendly building materials. It is very important, and this is something that we already see coming.

Do you consider these ideas to be realistic or are they more of a dream situation? Considering the economical problems of a shrinking tax base due to a smaller working part of the population, who would pay for the transformation?

Now, these examples I gave are of course part of a development that I would love to see. But if you ask me to be realistic... then unfortunately I don't think so much will change in Tokyo during the coming 40 years. Maybe in the next 80 years, but by then I might not be alive anymore. And even during my life time, will I be able to contribute to an urban development that I find good and sustainable? I have my dreams, but I don't know if they are realistic.

What happens to buildings if nobody lives there? They decay. Nature will take back what was once nature's. We all know that decay in cities is a big question. And eventually, looking at that cycle of revitalization and rediscovery... Who will rediscover it? Maybe not human kind? I don't know. That is a different story. I don't know how to deal with this in an architectural sense. But some things will just not be controllable. Even if we put in money to build a shopping centre, and no one comes, then it will close down. That's the end of the story, unfortunately, of what urban planning can do.

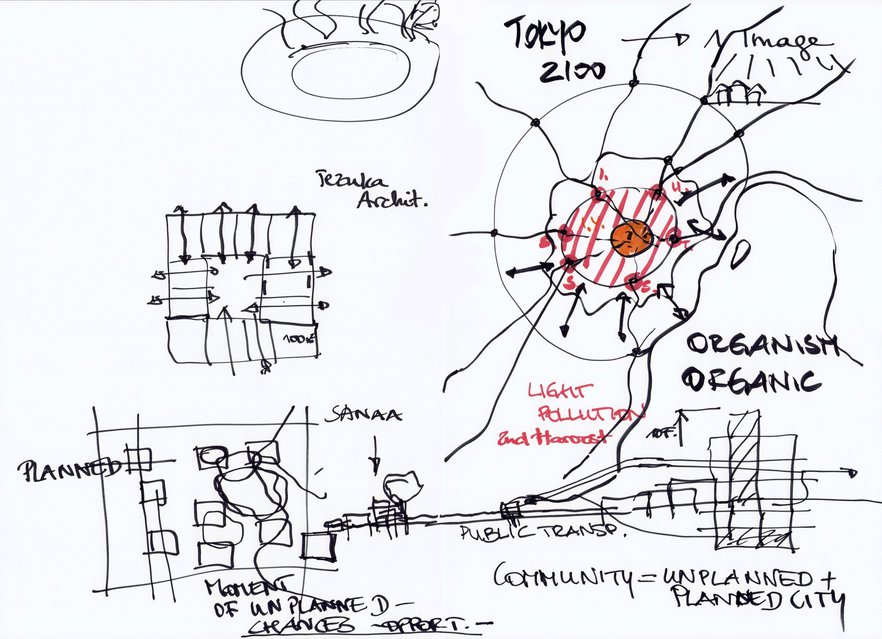

TOKYO'S FUTURESCAPE ACCORDING TO HEIDE

I would like to start by zooming out to the bigger scale. There are train rails, like arteries, that take away the urban sprawl. There is a core, and then you have another core in a second ring. I like the idea of not having only one empty center, but various sub-centers. There is also a kind of a shrinking-growing effect, like a cell membrane that adjusts itself all the time, like an organism.

And now, if we zoom in... Within Tokyo there are many different versions of living styles. But let's choose a random place and have a look at a specific courtyard. People live around this central courtyard, inspired by the Tezuka architects. This house is open to the sides and it has adjustable walls. You can adjust the border between inner and outer space. Many people can share this space. I think just one family is too isolated. So maybe 100 m2?

It would be nice to create a bigger version of this home, like a town. A small community within the community, a bit like the SANAA architects have tried to do with their very tiny blocks. Maybe a puzzle of buildings like this. And then people can decide in their own way on how they want to access each other's space or create community. However, you also need that moment of the unplanned. I don't want to say "void" because it is not empty. But if you would see the map in a 3D version you would see that there are of course places with much lower density. If there is an emptiness somewhere in between the sub-centers and the railway stations, then maybe something new emerges.

Heide Imai